( A very brief history)

Rabaul in the years after the First World War was a thriving

township. Harry Morris, a long time resident of Rabaul states in his memoirs:

But nevertheless the Mandate prospered, and Rabaul blossomed into an

administrative centre of some note. The European population grew to about

a thousand, the houses were relatively comfortable, and the streets were

tree lined, especially Malaguna Road and Mango Avenue, where the mango trees

formed an overhead arch of shade stretching from side to side, so that it

was possible to pick and eat a mango walking to work. Roads were reasonably

well constructed with large hand pitched stone drains on either side. Recreation

facilities were encouraged, especially the town swimming pool that was connected

at high tide with the waters of Simpson Harbour.

The most significant pursuit in the town was shipping. Two reasonable wharves

took shape with continuous warehouses to serve the activities of three Australian

shipping companies that were active throughout the whole Pacific region,

namely Colyer Watson, Carpenters, and Burns Philp.

Rabaul has active volcanoes in its environs. In 1937 a large eruption covered

the town in ash and debris, the same happened in 1941 and the last eruption

in 1994 has all but ruined Rabaul.

Being a mandated territory the Australian Government was not allowed to fortify Rabaul. In 1939 with the outbreak of war in Europe the Australian Army allowed the white population to form the New Guinea Volunteer Rifles (NGVR). Unlike the Germans in 1914,the Australian administration did not allow the native population to join. Due to its strategic position and the threat of war with Japan, on the 18 February 1941 the Australian Government decided to send a battalion of the Australian Army to Rabaul. The 2/22nd battalion (Lark Force) of 1400 men arrived in Rabaul in March 1941. Shortly after the arrival of the 2/22nd battalion, the 2/10th-field ambulance that included six nursing sisters K.I.A Parker, M.J.Anderson, D.C.Keast, L.M.Whyte, M.C.Cullen and E.M.Callaghan arrived to take care of the medical needs of the men.

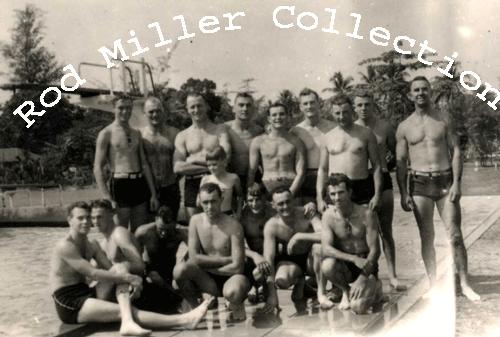

William Hughes and men of the 2/22nd Battalion-Rabaul 1941

If anyone viewing these pictures can identify any of these men could you

please write.

It is possibly members of A Company.

Update.

21/5/2009

Jeff Smith writes:

Re Photo, members of A Co. Back row, far right, arms folded is my father,

Sgt. F.S.Smith.

The Australian government

on the 11th December 1941 endorsed that there should be no compulsory evacuation

of Rabaul. Then the very next day it reversed this decision. It is known

today that the Japanese naval codes had been broken prior to the war. Is

it possible that the Australian government knew of the intention of the

Japanese to take Rabaul? Most of the European women and children were evacuated

from Rabaul on the 22nd December. The nurses at the government hospital

were offered evacuation but as a matter of duty stayed in Rabaul. The army

nurses weren't offered evacuation and remained with the men. Some of the

missionary and civilian women remained in Rabaul. The Norwegian cargo ship

Herstein

had arrived early in January 1942 it was loading copra when the first Japanese

air raid occurred on the 21st January 1942. It was bombed and its load of

copra burnt for 3 days.

William Hughes and men of the 2/22nd Battalion-Rabaul 1941

With the bombing of Rabaul and the sinking of the Herstein the men and women left in Rabaul were effectively cut off from Australia. Although they didn't know it the Australian government had already made the decision that the men in Rabaul were to be regarded as hostages to fortune.

Rabaul swimming pool 1941

Update.

21/5/2009

Jeff Smith writes:

Photo, Rabaul swimming pool, back row, 3 rd. from left, arms folded again,

is my father, Sgt. F.S.Smith.

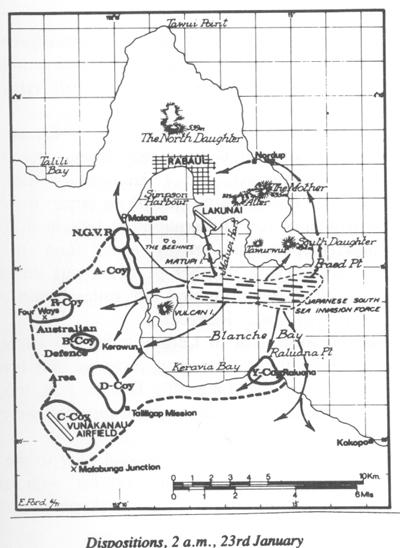

When the Japanese attacked with 5000 men on the 23rd January 1942, the men of the 2/22nd Battalion had little chance of defending Rabaul. The sheer size of the harbour area meant that the Japanese met little resistance in some locations.

Deployment of 2/22nd Battalion & NGVR when attacked 23rd January 1942

The men of the 2/22nd battalion put up a gallant fight but inevitably they were over run. The order "every man for himself" was given and the men who had survived the battle tried to escape down the North and South coasts of New Britain. No provision had been made for the escape of the battalion. Without food in the tropical conditions the men faced great difficulties escaping. When the Japanese dropped pamphlets declaring that they would be treated as prisoners of war many surrendered. Some were returned to Rabaul, but approximately 150 men were executed at Tol plantation on the shores of Wide Bay.

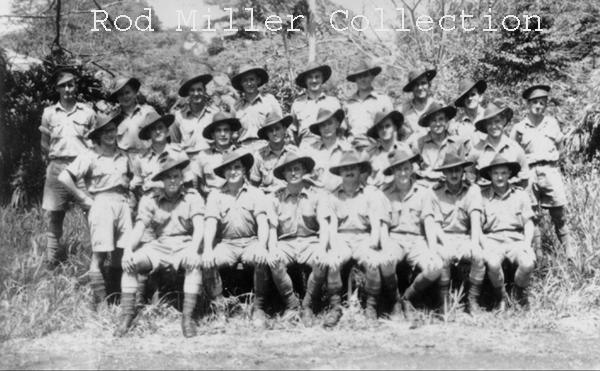

Photograph of the men of the 2/10th Field Ambulance.

Billy Cook & W.D Collins survived TOL. 3 Men incl. Maj. E.C. Palmer

escaped on the Laurabada.

One left before the invasion. Cpl. L.A Hudson & Pte R.M. Langdon

stayed with the nurses till taken to Rabaul. Most died at Tol or on the

Montevideo Maru.

Two groups of men did escape New Britain. One from the North Coast the other from the South coast. These men Included the two survivors of Tol, Billy Cook and W.D.Collins.

By March 1942 Malaya and Singapore had been captured. One of the civilian POWs in Rabaul was Gordon Thomas. Gordon was the editor of the Rabaul Times news paper and one of only four who survived the war with the Japanese in Rabaul.

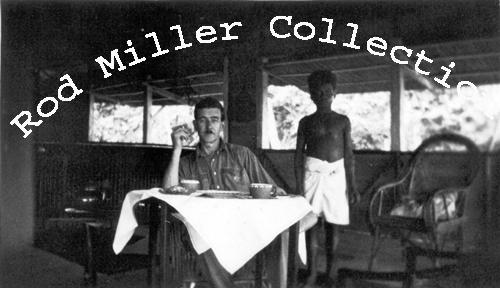

Early photograph of Gordon Thomas

In May 1942 Gordon Thomas notes that the Japanese gathered all the Pows, Army and Civilian for the purpose of collating nominal rolls. He states that this was for the purpose of handing the prisoners from the jurisdiction of the Japanese Army to the Japanese Navy. It was also at this time the Japanese allowed the prisoners to write letters home. The letters were dropped in a bag over Port Moresby air strip by a Japanese plane. These letters were to cause a lot of confusion at the end of the war for although no further information was ever received in Australia the relatives of the POWs expected that their loved ones would be liberated in Rabaul.

Letter sent by Pvt Allan Tumman to his parents.

Why did the Japanese allow the POWs in Rabaul to write letters home? I personally believe that it was a form of propaganda. The Japanese were trying to portray themselves as civilised, caring individuals who looked after their prisoners of war. It must be remembered that when these letters were sent in May 1942, only 5 months after the bombing of Pearl Harbour. The Japanese were yet to loose a battle. At a political level internee exchange was being negotiated so it was important that the right impression be sent to the Australian public. The problem for the Japanese was that the survivors of the Tol massacre escaped back to Australia and were telling of their ordeal.

At the end of the war no trace of the POWs from 1942 could be found in Rabaul, except for Gordon Thomas (editor of the Rabaul Times), A.D. Creswick (engineer), G. McKechnie (engineer), J. Ellis (electrical contractor). The only others were the missionaries from Vunapope Catholic Mission who had moved to the Ramale valley when the mission was destroyed by Allied bombing, J.J Murphy (captured coast watcher) and some Allied airmen who had been shot down over Rabaul..

L to R Creswick, Thomas, McKechnie, Ellis on liberation 1945.

So why is it out of the 1050 POWs in Rabaul in 1942, only these 4 were found alive in Rabaul at the end of the war? Creswick, McKechnie and Ellis had knowledge of the Rabaul power generators and ice works. In the beginning, before these utilities were levelled by bombing, these men were required by the Japanese to keep the equipment running. But Thomas was a Journalist. Why did the Japanese select these men to live when all the others died? There was a reason Gordon Thomas was kept in Rabaul by the Japanese and didn't die with the other prisoners.

So what happened to the other 1053 prisoners

of war that were in Rabaul in 1942?